Welcome to the 15th edition of First Nations News & Views. This weekly series is one element in the "Invisible Indians" project put together by navajo and me, with assistance from the Native American Netroots Group. Last week's edition is here. In this edition you will find a condensed history of the Narragansetts, the tribe whose ancient lands Netroots Nation participants will be holding their conference on in early June, a look at the year 1895 in American Indian history, two news briefs and some linked news bullets. Click on any of the headlines below to take you directly to that section of News & Views or to any of our earlier editions.

Invisible Indians at Netroots Nation

By Meteor Blades

![Fanciful view of Roger Williams meeting the Narragansett in 1636.]()

Fanciful view of Roger Williams meeting the Narragansett in 1636.

When participants at the Netroots Nation annual conference head out for dinner in Providence, R.I., less than three weeks from now, one of the menu items they'll see everywhere will be quahog chowder and, for the really adventurous, exotic dishes like jalapeño-stuffed quahogs. These delicious clams can be found elsewhere, from Prince Edward Island to the Yucatán peninsula. But they got their name from the people who lived in Rhode Island ages before the colony was a gleam in Roger Williams's eye - the Narragansetts.

Though there are some 2400 tribally enrolled Narragansetts living in Rhode Island today, many of them feel they are, like Native people elsewhere in the United States, invisible. Small wonder. Just 20 miles south of Providence, in Exeter, is a museum devoted to the culture of the Narragansetts and Wampanoags, who also live in Rhode Island, just as they did before the first Europeans stepped onshore. Seventy percent of the museum's visitors are surprised to learn that neither tribe is extinct. Despite hundreds of years of prodigious work to extinguish them - to take their land, their culture, their language - they live on. But I'll get to all that momentarily.

![Photobucket]()

Quahog comes from the

Narragansett word poquauhock

Still visible throughout Rhode Island today are linguistic hints of the Narragansetts' presence. In their Algonquin language, the name for quahog was

poquauhock. Similar words can be found in the tongues of other Indians in the region, like those Wampanoags, the Narragansetts' neighbors who kept the Mayflower Pilgrims from starving during their first grim winter 50 miles to the east.

All around Rhode Island, Narragansett words name towns, bodies of water, islands and streets. The word "Narragansett" itself, which is an apparent English corruption of Nanhigganeuck, means "small point of land." There's Pawtuxet ("Little Falls") Village, which will commemorate its 375th birthday next year, one of the oldest villages in New England. The Hotel Manisses on Block Island takes its name from what the Narragansetts called that island, the "little god place." A ride to the north edge of the city will take you to Wanskuck ("the steep place") Park.

![Photobucket]()

Succotash comes from the

Narragansett word msíckquatash

If you want to add some vegetables to your quahog selection (or if you are vegan), you might try succotash, (

msíckquatash: "boiled corn kernels") or squash (

askutasquash: "a green thing eaten raw"). Thanks in part to Roger Williams's study,

A Key Into the Language of America, a handful of Narragansett words didn't just remain in New England. There are, for instance, papoose (

papoos: "child") and moose (

moos: the well-known member of the deer family). Plus a word far removed today from its original meaning, powwow (

powwaw: "spiritual leader.")

Here you can see Narragansetts dancing at their August 2011 Powwow.

Today, the descendants of the Narragansetts live throughout Rhode Island. Their tiny reservation is at Charlestown, just 1800 acres (2.8 square miles) surrounding the three acres that was once all the tribe had left. Some 60 tribal members reside there now. That in itself is practically a miracle given the more than three centuries settlers and militias and government bureaucrats spent trying to obliterate the tribe. In addition to the 2400 enrolled members, there are perhaps another 2000 or so people in Rhode Island and the rest of the United States who can trace their line to a Narragansett ancestor.

The inevitably flattened nuance that is a consequence of compressing the tribe's long past into a few paragraphs no doubt would make historians cringe. But even a few words can help bring the invisible into the light. Readers interested in something more thorough can find it here, here, in The Narragansetts and in Robert Geake's A History of the Narragansett Tribe of Rhode Island: Keepers of the Bay, just out last year in paperback. Except for Simmons's book, which I've only just begun reading, I've adapted the next dozen paragraphs freely from these and the linked sources in the text.

First Encounters

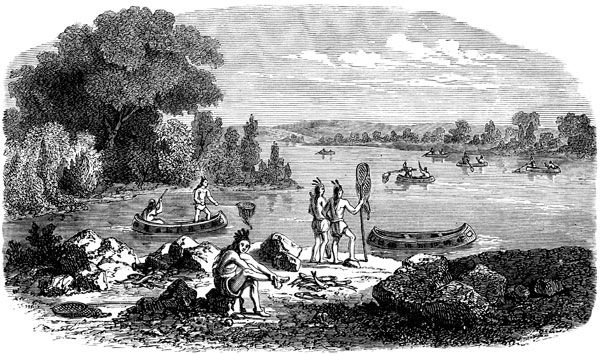

By the time, the Italian explorer Giovanni da Verrazzano cruised the coast around Narragansett Bay in 1524, there had been people in the area for thousands of years. Just how many thousands has long been disputed. Contact for the next few decades was so infrequent that even "sporadic" doesn't cover it. But in 1617, that contact had similar consequences to what had happened when Hernando de Soto meandered through the South and Hernán Cortes pillaged his way through Mexico: plague. The bacterial infection leptospirosis is now believed to have been the culprit. Whatever it was, huge percentages of the tribes in Massachusetts were wiped out in just three years. Tisquantum, the Pawtuxet Indian we know as "Squanto," became the last of his tribe because he wasn't around for the plague to kill him.

The Narragansetts were fortunate. They were barely affected by the plague. Already strong before the illness struck down their rivals, by the time the Mayflower landed its passengers at Plymouth in 1620, they were the most powerful tribe in southern New England, comprising perhaps 10,000 people. They were enemies of the Wampanoag, the "Thanksgiving" Indians, and the Pequot, with whom they fought regularly. The English, who they called ciauquaquock ("people of the knife"), would not trade with them directly.

In 1636, Roger Williams, who openly said colonists had no right to take Indian land was forced out of Massachusetts. He bought land from the Narragansett and ushered in a period of trust between him and the Narragansett that lasted until his death near half a century later.

That trust was early on reinforced when the Narragansett briefly joined the Puritans in a three-year war against the Pequot. In the last year of that war, 1637, the English slaughtered hundreds of Pequot women, children and the elderly by burning them alive inside their palisade fort at Mystic River and selling the survivors into Caribbean slavery. In disgust, the Narragansett went home. Although they gained some benefit from the war, their Mohegan rivals under the sachem Uncas, who had also allied with the English, got the most.

The Narragansett sought to maintain their superiority in southern New England, but events ran out of their control. Over the years of shifting alliances and steady English immigration, many skirmishes occurred, there were a couple of real battles, and the Narragansett wound up paying annual tribute to the English. But they remained good friends with Williams. He was still considered a radical outsider by the Puritans, who excluded Rhode Island from the New England Confederation in 1643. Isolated, their traditional turf threatened by a tribe the English protected, the Narragansett grew weaker every passing year.

![Narragansett seal]()

In 1675, Metacomet, the Wampanoag sachem known to the English as "King Philip," became fed up with continuing English expansionism onto Indian land, the aggressive conversion of Indians to Christianity and other injustices. He began negotiating with allies and traditional rivals, all these tribes now vastly reduced by waves of epidemics over the decades. By the time Metacomet decided on war with the English, the Narragansetts numbered perhaps 5000.

The sachem began his attacks and the English countered. Surrounded on all sides by people they did not trust, the Narragansett remained neutral for the first six months of what we call King Philip's War. But they took Wampanoag refugees into a fort they had constructed for themselves and waited things out. The English in pursuit of Metacomet left them alone. But he managed to elude them and make his way back to the fort, soon departng with most of the Wampanoag refugees. The English saw this as a violation of neutrality and sent 1,000 colonial troops and 150 Mohegan scouts to lay siege. In the fighting, the Narragansetts lost 600 warriors and 20 sachems.

The principal Narragansett sachem, Canonchet, continued to fight in alliance with Metacomet. But returning on a mission to obtain seed corn he was captured by Mohegans and handed over to the English who promptly sent him to a firing squad.

King Philip's War was at first a close thing. Some scholars say the allied Indians had a narrow possibility of driving the English out altogether. But after nine months, the insurgent tribes, outnumbered from the beginning, were running short of food, gunpowder and warriors. Metacomet was hunted down, shot in the heart, hanged and then decapitated. His head was sold for 30 shillings.

The Narragansett Fight to Keep Their Identity

![Bella Machado-Noka, reigning champion of the Eastern Blanket Dance]()

Bella Machado-Noka, reigning champion

of the Eastern Blanket Dance

And the Narragansett? After Canonchet was executed, the 3000 survivors had been mercilessly hunted down. Warriors were almost always killed. Women and children were sold into slavery in the Caribbean. Some managed to join other tribes, particularly the Eastern Niantic around Charlestown, who had remained neutral. By 1782, only 500 Narragansett were left to sign a peace treaty with the English. Some emigrated to Wisconsin in the late 1780s, but the main body remained in Rhode Island.

In 1830 the state sought to portray the them as unworthy of being called Indians. "Forty years ago this was a nation of indians now it is a medly [sic] of mongrels in which the African blood predominates," read a report from a committee of the legislature. The real motivation behind this claim could be found in the recommendation that a white overseer be appointed and the land be sold for "publick uses" as soon as the tribe was deemed extinct.

The legislature tried again in 1852. A report stated: "While there are no Indians of whole blood remaining, and nearly all have very little of the Indian blood, they still retain all the privileges which belonged to the Tribe in ancient times." And those, it said, should be extinguished. The Narragansetts successfully resisted.

In 1866, they resisted again. This time, that resistance against the effort to break up their tribe and make them citizens was couched in language that explicitly attacked racial prejudice:

"We are not negroes, we are the heirs of Ninagrit, and of the great chiefs and warriors of the Narragansetts. Because, when your ancestors stole the negro from Africa and brought him amongst us and made a slave of him, we extended him the hand of friendship, and permitted his blood to be mingled with ours, are we to be called negroes? And to be told that we may be made negro citizens? We claim that while one drop of Indian blood remains in our veins, we are entitled to the rights and privileges guaranteed by your ancestors to ours by solemn treaty, which without a breach of faith you cannot violate."

The Narragansett had responded that they were a multiracial nation, culturally Indian, thereby turning the emerging "one-drop" rule on its head. Once more, their resistance succeeded.

But in 1880, just as the federal government would seek to do with all the tribes, Rhode Island detribalized the Narragansetts. This was illegal under federal law, but Washington did not intervene. At the time, there were 324 people the state considered part of the "mongrel" tribe. The government broke up the reservation, sold the remaining 15,000 acres at auction using most of the money to cover incurred debts, and leaving only the three acres around the Indian church founded in 1744. The state ended all treatment of the tribe as a political entity.

Despite detribalization, however, the Narragansetts took great pains over the next half century to continue meetings and ceremonies, maintaining the customs as best it could under trying circumstances. In 1900, it incorporated. After the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934, the Narragansetts began the long process of regaining tribal status.

Modern Times

It was not until 1975, however, that the tribe filed a federal lawsuit seeking restoration of 3200 of the acres taken nearly a century before, five square miles. Three years later, it signed an agreement with Rhode Island, the muncipality of Charlestown and white property owners for 1800 acres to be turned over to the tribal corporation and held in trust for the descendants of the 1880 Narragansett Rolls.

![Narragansett Indian Chief Sachem Matthew Thomas, right, tries to hold back a Rhode Island State Police officer from entering the Narragansett

Indian Smoke Shop in Charlestown, RI]()

Narragansett Sachem Matthew Thomas, right,

tries to hold back a Rhode Island State Police officer

from entering the Narragansett Indian Smoke Shop

in Charlestown, R.I., in 2003. The tribe claimed it had

the sovereign right not to collect taxes there.

But there was a catch. Except for hunting and fishing, all the laws and rules of Rhode Island would apply because the tribe did not yet have federal recognition. It got that in 1983 and officially became the Narragansett Indian Tribe of Rhode Island. But, while recognition provides the tribe with some financial and other benefits from the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the 1978 pact with the state, city and local residents stands in the way of anything approaching real sovereignty. The Narragansetts can't build a casino or sell cigarettes without paying taxes on them as other tribes can do. If a tribal court were established, it wouldn't even have jurisdiction over violation of traffic laws on the reservation.

The lack of sovereignty was punctuated in 2009, when U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the Narragansetts and other tribes in the case of Carcieri v. Salazar. The tribe had purchased 31 acres that it wished to have brought into federal trust lands governed by the Department of Interior. The department agreed to do so. Rhode Island appealed administratively and then in the courts, losing until the case reached the Supreme Court. The state argued that the vague wording of the Indian Reorganization Act did not allow the federal government to transfer land into federal trust for tribes that were not recognized before 1934. The Court agreed in a decision affecting not just the Narragansetts but 30 other tribes. Since then, bills have been drafted for a legislative "fix," but none has yet emerged from committee. President Obama has made a statement hinting that the Department of Interior should be able to transfer land to tribes recognized after 1934, but the executive branch cannot take unilateral action. Meanwhile, the Charlestown Citizens Alliance and the RI Statewide Coalition continue to oppose anything that would give the Narragansett more control over their own affairs.

Thus, politically, the Naragansetts remain in a kind of tribal limbo, without the full rights of other tribes, but better off than the many unrecognized tribes with no rights at all.

Culturally, it's a different matter. The Narragansett know who they are. All that resistance in the face of great odds has bound them together in pride over the generations. While their blood mingled, their spirit and unforgotten traditions has kept them united.

![Photo f Lorén Spears, curator of Tomaquag Museum]()

Lorén Spears, curator of Tomaquag Museum

One of the keepers of the flame today is Lorén Spears (

Narragansett), the executive director of that museum in Exeter I mentioned. It's the

Tomaquag Indian Memorial Museum,

tomaquag being the Narragansett word for "he who cuts," the beaver, an animal that once thrived throughout Rhode Island in great abundance.

The museum's exhibits focus on the Narragansetts' past, both distant and recent, but its mission is educate everyone, including Waumpeshau (white people), about Native history, culture, art and philosophy:

[Visitors can explore] Narragansett history through The Pursuit of Happiness: An Indigenous View, which reflects on the denial of our rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. The exhibit focuses on Education, Spirituality, Political and Economic Sovereignty, Love and Family, and the importance of traditional language.

Visitors can also learn about Narragansett notables like marathon runner Ellison "Tarzan" Brown, known as Deerfoot among his own people. He won the Boston Marathon twice, once in 1936 and in 1939. He was the first ever in the Boston event to break the 2:30 mark (2:28:51). He was also at the Berlin Olympics in 1936.

Citing the marathon historian Tom Derderian, Gary David Wilson writes of Brown:

He was regarded by most as a freak - undisciplined and uncontrollable, a child of nature, an awesome natural talent - and if he won or lost it was because of his unalterable nature. Thus, as an Indian with physical gifts, he would never get personal credit for what he accomplished. It was expected he could run - he was an Indian, after all - so he got no credit for character, courage or work ethic. If he succeeded it was because he did what his handlers prepared him to do, like a thoroughbred racehorse. When he failed, it was his own fault, because he was "just an Indian."

As Wilson says, few even in the running community know of him today, though there is now a book on his life.

The museum is only part of Spears's work. Her teaching background with at-risk kids spurred her to establish the Nuweetoun School adjacent to the museum to teach kindergarten through 8th grade children in a supportive environment that adds Native culture and history to all areas of study. For her work, she was chosen as one of 11 Extraordinary Woman honorees for 2010 in Rhode Island. Writes Leslie Rovetti:

The building that houses the school used to be her grandparent's business, the Dove Crest Restaurant, which served raccoon pot pie, cornmeal pudding, cod cakes, succotash, venison and native clam bakes, in addition to more common foods like steaks and "the most amazing double-stuffed potatoes," Spears said. When the building that was the restaurant's gift shop became the museum, she said her grandmother was on the founding board.

Because of flooding, the school is on hiatus. But Spears is busy with a new grant-funded project, building a curriculum the tribe would like to be used throughout all schools in Rhode Island. The curriculum would be used together with the film, Places, Memories, Stories & Dreams: The Gifts of Inspiration. Spears says she remembers "being in a history class during my elementary days and actually reading that I supposedly didn't exist, that my family didn't exist, that my people didn't exist."

The film features traditional Narragansett stories and an oral history presented by tribal elder Paulla Dove-Jennings (aka SunFlower), a renowned Indian storyteller. Once the project is complete, the film's six segments narrated by Dove-Jennings will be organized within the 43-page curriculum. That will be available for downloading from the museum's website, free to teachers who want to use it for lessons.

If the curriculum comes to be widely used in Rhode Island schools, it might go a long way toward ending the Narragansetts' invisibility in the very place they lived for so many milleniums. That would be a very good thing.

Indeed, no reason exists why such a curriculum couldn't be developed for every school district where Native people once lived and many still do, even if nobody notices until there's trouble. But widespread adoption of such curriculums tailor-made to local circumstances means discomfort for many people when Indians and all we represent in this country - culturally, politically, historically - emerge from invisibility. Strong opposition could be expected. What are they afraid of after all these years?

![Invisible Indians Banner for NAN]()

(First Nations News & Views continued below the frybread thingey)

This Week in American Indian History in 1895

By Meteor Blades

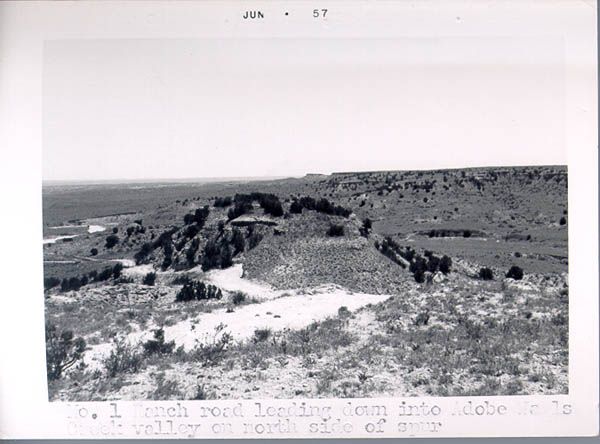

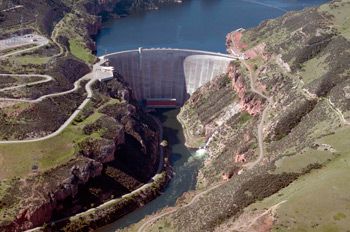

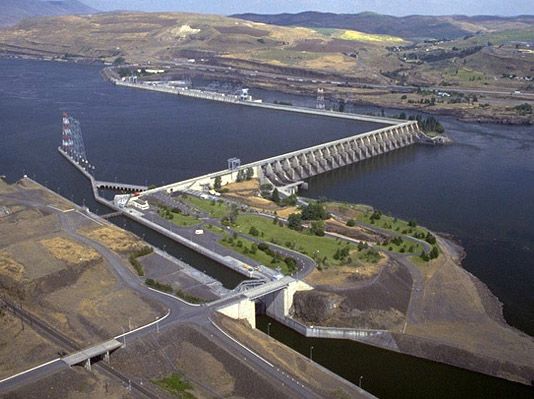

On May 23, 1895, the smallest and last federally approved land rush in Oklahoma Territory got under way as "surplus lands" of the Kickapoo were thrown open for settlers to homestead. That rip-off had begun in 1889.

The Kickapoo had fled their homeland in southwestern Wisconsin after the Blackhawk War in 1832. By a circuitous route over many years, they had wound up in Indian Territory. The territory had been the turf of Caddo, Osage, Kiowa, Kiowa-Apache, Wichita and Comanche. But in the 1830s, it became the new home of the "Five Civilized Tribes" who were removed at gunpoint from their east of the Mississippi homelands. Over the next several decades, 20 more tribes were shipped to what became Oklahoma.

In 1889, there were in the western part of the territory areas originally meant to be filled with other removed tribes, two million acres of so-called "Unassigned Lands." As part the Indian Appropriation Act of that year, those lands were set aside for white settlement. Out of that came the first Oklahoma land rush.

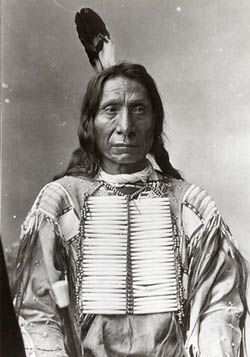

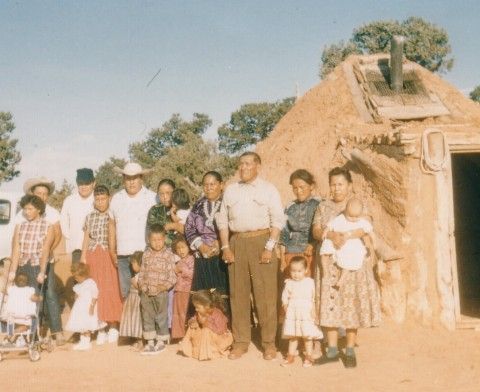

![A Kickapoo family photo taken

in 1898 by Rinehart]()

A Kickapoo family photo taken in 1898 by Rinehart

Also in 1889, the

Cherokee Commission or Jerome Commission was established. It was a tribunal, comprising two generals and a civilian. But the chief negotiator was David Jerome. His mission was to legally acquire Indian-owned lands. In practice, this meant intimidating the tribes into dissolving their reservations and accepting allotment under the Dawes Act of commonly owned land to individual Indians in 80- to 320-acre plots. What was left over after allotment, the so-called "surplus," was sold to the government at the government's price. This surplus was then opened up to homesteaders, 15 million acres in all, in a series of land rushes.

The corruption involved - with sheriffs, their deputies, minor federal officials and others getting a head start on the best land, the so-called "Sooners - is a story for another time. For the Indians, that part is irrelevant. It was all over for them when they were agreed or were forced to sign away their rights. By June 1890, agreements had been "obtained" from the hold-outs, the Iowas, Sacs and Foxes, Pottawatomies, and Absentee Shawnees. Only the stubborn Kickapoo remained.

After a commission visit with the Kickapoos, Jerome wrote to his superiors on July 1:

The Kickapoos are altogether the most ignorant and degraded Indians that we have met, but are possessed of an animal cunning, and obstinacy in a rare degree. We were prepared, by what we had heard before our coming for an exhibition of these qualities. [...]

The Commission, each member in turn, made speeches to them, explained our business with them, told them of the impending changes in their mode of living, earning a living &c, and submitted to them a proposition in writing, which is hereto attached and made a part hereof, and placed a copy of it in the hands of the Chief, and asked them to go with their Interpreter and consider it. [...]

When the paper, containing the proposition, was placed in the hands of the Chief, the Kickapoos seemed to become somewhat uneasy-a little Indian jargon was exchanged-when he, the Chief, handed back the paper and refused to keep it. They then took their leave, and promised to return in the afternoon. At the time appointed they came back, and promptly told us, that they would not make any contract, because it would offend the Great Spirit.

Jerome went on to say that if the president were to set a deadline for allotting land, this would speed the process with recalcitrant tribes.

A year later, the commission met with the Kickapoos again, this time letting them know that the allotment process was going to happen whether they wished it or not. So, they should sell and get the best deal they could. Hence it was considered better to let the white crowds overrun the reservation than to sell it. Ock-qua-noc-a-sey was the chief speaker of the Kickapoo. He had a lot to say about the land being given by the Great Spirit who would be angry if the Kickapoos sold it. The allotment deal was something that came "someone under the earth," he said, adding that the Kickapoos would be better off to let the whites overrun it than sell it. "Whenever the white people take all the land from the Indians," he said, "we believe the land will be destroyed. [...] We have a small reservation here and you have the biggest part of the United States; and you should be satisfied and we are doing well."

Dissident Indians from the tribes that had already been forced to sign came to warn the Kickapoos not to "touch the pen." And Ock-qua-noc-a-sey and others who had been speaking did not. On June 18, they got up from the negotiations and went home.

Later, all but three of the adult male Kickapoos showed up for another meeting. Four had already signed the allotment agreement. Others seemed ready to sign. But then Chief Wape-mee-shay-waw showed up, and after some talk, all but the signers came to the chief's side. The commission had failed.

But, in August, at the instigation of John T. Hill - who, wrote Berlin B. Chapman in 1939, was probably as much Kickapoo as David Jerome - Ock-qua-noc-a-sey and Kish-o-corn-me signed the allotment deal and used dubious power-of-attorney to sign for 51 other Kickapoos, the adult male population of the tribe in September 1891. So seven men, one of doubtful heritage made a deal for the whole tribe. Washington considered the document binding. The majority of Kickapoos did not, and they continued to resist right up until the allotments were handed out three years later.

Of 206,080 acres on the reservation, 22,640 acres were allotted to 283 Kickapoos, 80 acres each by March 27, 1895. The remaining 183,440 acres purchased by the federal government were opened to settlers in a land run. The Kickapoo lands were added to Lincoln, Oklahoma and Pottawatomie Counties.

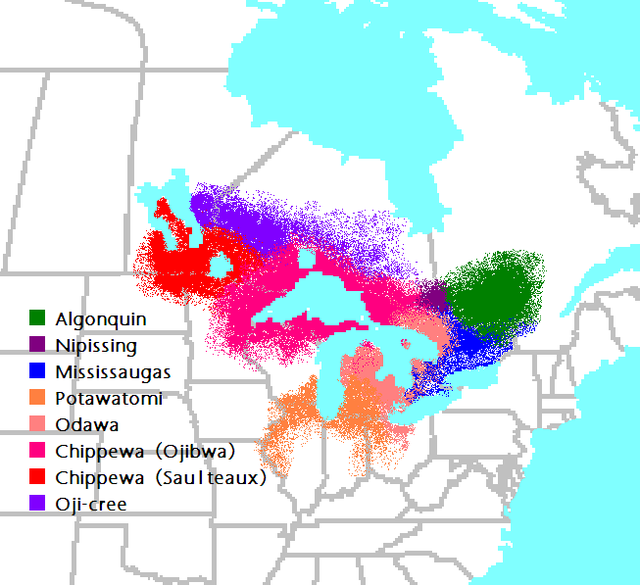

Today, the Kickapoo Tribe of Oklahoma, federally recognized since 1936, has 2,720 enrolled members, some 1800 of whom live in the state. About 400 Kickapoo, including children, speak the tribe's Algonquian language. Two other federally recognized Kickapoo tribes totaling a few hundred enrolled members live in Kansas and Texas.

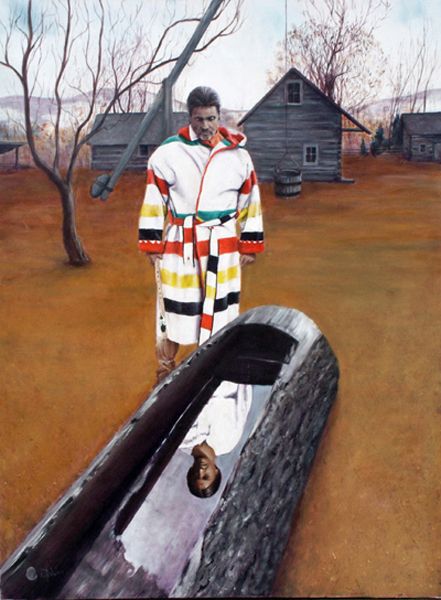

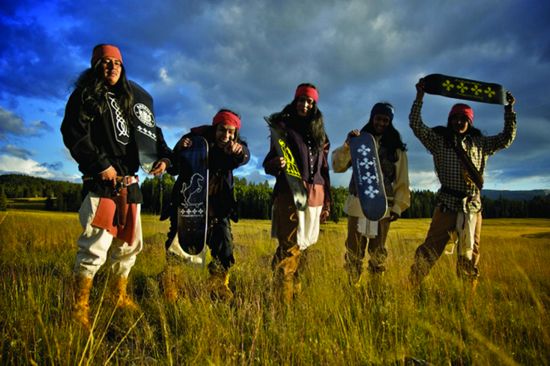

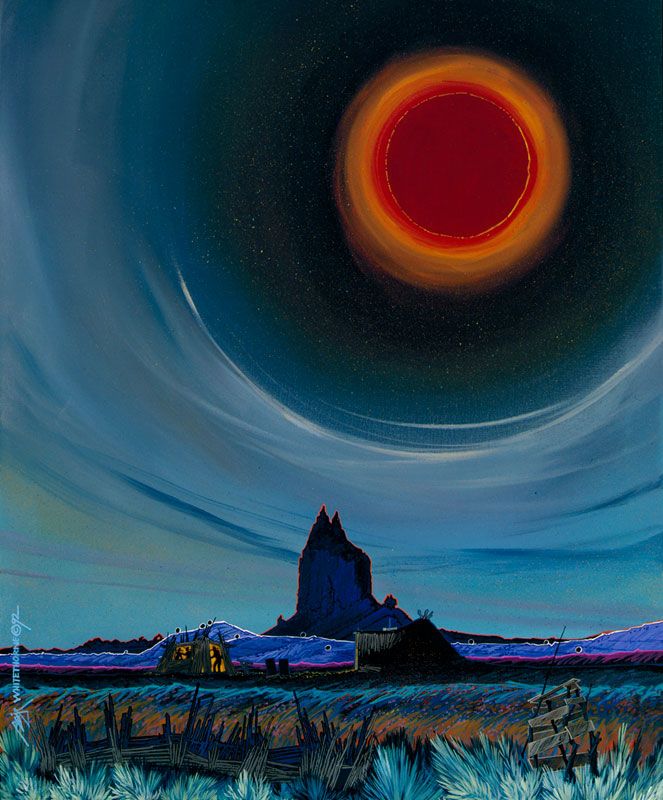

Navajo Artist Tony Abeyta is a "Living Treasure"

By navajo

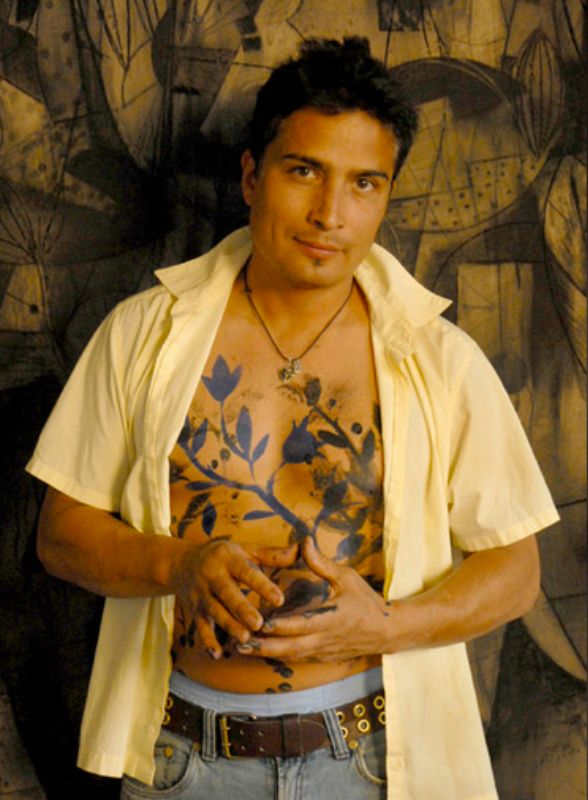

![Photobucket]()

Tony Abeyta

-Photo by Jennifer Esperanza

Every year, the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe holds the

Native Treasures Indian Arts Festival.

Tony Abeyta (

Navajo) is being honored as this year's "living treasure."

At age 46, Abeyta finds it a little strange to be considered a living treasure. He was selected for "his style, his time spent mentoring other young Native American artists and his refusal to fall back on formulas when it comes to creating art. Abeyta is among the artists who are pushing the envelope when it comes to redefining American Indian art."

Abeyta grew up in Gallup, N.M., but left at age 16 to attend the Institute of American Indian Art in Santa Fe. He has studied art across the nation as well as in France and Italy. He now has studios in Santa Fe and in Chicago. In addition to oil paintings, Abeyta also works on large-scale drawings, large sculptures and designing jewelry.

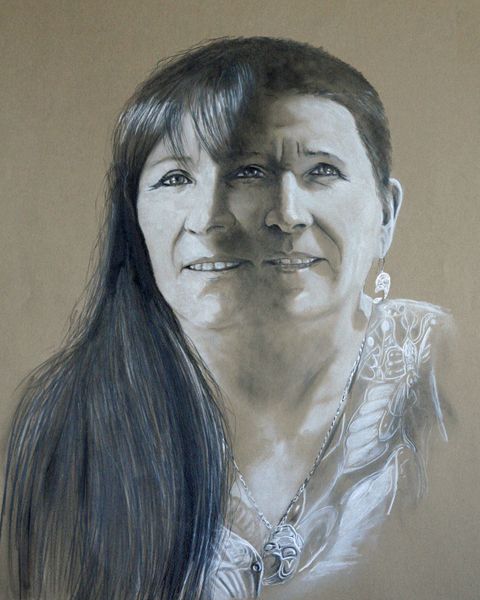

![Photobucket]()

Thumbnails of Tony Abeyta's art

![Photobucket]()

Narciso Abeyta

His father, Narciso Abeyta, was also an artist. Born in 1918, he began his art career at the early age of 11 by drawing his first creations on canyon walls on the land of the Navajo Nation. By 32 he was published in Art in America. During World War II, he was one of the famed Code Talkers. He walked on in 1998.

The festival opens May 26. More than 200 native artists from some 40 tribes and pueblos have been invited to the two-day festival. A wide range of art forms - pottery, carvings, jewelry and more - will be on display, much of it for sale. There will also be an "Emerging Artist" section to showcase new talent.

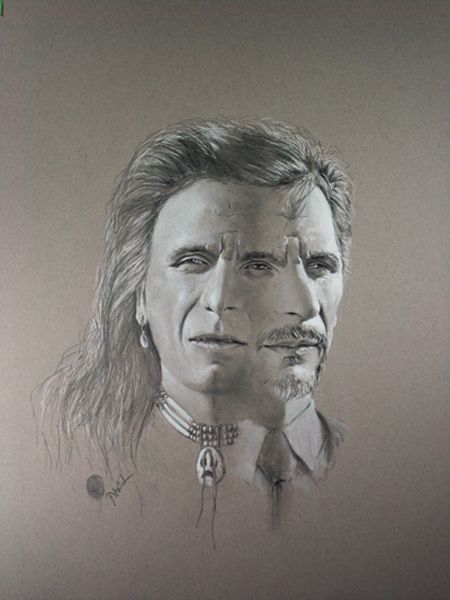

![Photobucket]()

Thumbnails of Narciso Abeyta's art

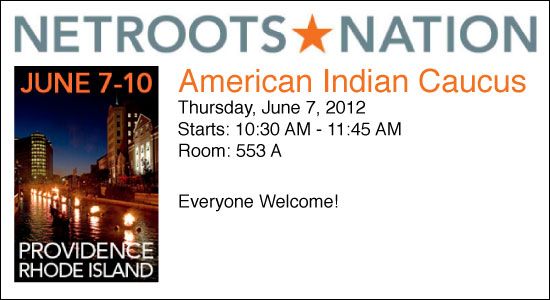

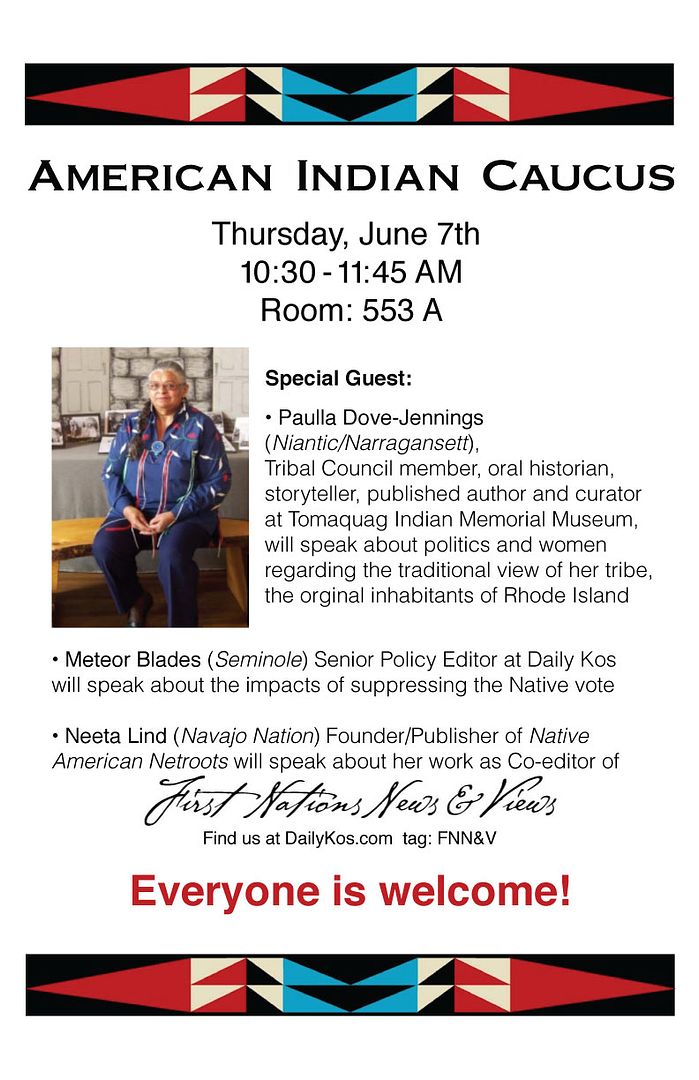

Day and Time for American Indian Caucus at Netroots Nation is Announced

By navajo

![NN12 American Indian Caucus]()

Meteor Blades and navajo are pleased to announce the date and time for the American Indian Caucus, which has been held every year since 2006 at Yearly Kos/Netroots Nation. Please join us! In light of the Elizabeth Warren controversy, we will be discussing and answering questions about what it is to be Indian, voter suppression on and near Native reservations and what can be done about it, and our experience in building First Nations News & Views.

navajo (aka Neeta Lind) will be giving a presentation again this year during the Promoting People of Color in the Progressive Blogosphere panel.

Friday, June 8, at 4:30 PM to 5:45 PM

This panel will address the needs, successes and obstacles to having greater participation from people of color in the blogosphere. Using the models of Native American Netroots and Black Kos as a beginning point for the discussion, we'll cover topics such as color blindness vs. representation and how to get historically underrepresented groups and their views heard. We'll discuss how to organize outreach between the larger blogosphere and blogs that are specific to communities of color and how to form stronger connections to ongoing organizing efforts and activism in communities of color. We'll also focus on how organizations can promote diversity within new grassroots organizations.

Another panel that was created to house the numerous proposals for voter suppression panels:

Protecting Voting Rights in Communities of Color in 2012

Thursday, June 7, at 4:30 PM to 5:45 PM

Black and brown voters turned out in record numbers in 2008. However, the introduction of voter ID initiatives in many states creates a new barrier for many Americans, particularly in traditionally disenfranchised communities of color. Voters in these communities-as well as students, seniors, the working poor and those with disabilities-will be most impacted. What coalitions and campaigns are underway to ensure these voters have equal access to the polls? How can we ensure that their voting rights are safeguarded and their voices counted? Panelists will provide case studies of campaign strategies and community solutions and tackle tough questions concerning voter ID laws.

![NAN Line Separater]()

• BIA Disputes GOP Claim About Violence Against Women: In their truncated reauthorization of Violence Against Women Act, House Republicans have relied on a House Judiciary Committee report which claims non-Indian offenders commit a "very small percentage" of domestic violence crimes on reservations. Citing this as a reason not to include better protection for Indian women on reservations as part of the VAWA renewal, Republicans last week rejected a proposed revision of the VAWA to allow tribal jurisdiction in cases of violence against women by non-Indian men on reservations. Since domestic violence on reservations is poorly handled by non-reservation jurisdictions, the women are pretty much left to fend for themselves. Michael S. Black (Oglala), acting director of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, said of the "small percentage" claim, "This is not true." Black wrote: "...the BIA recognizes that over half of all Indian married women have non-Indian husbands and that Indian women experience some of the highest domestic-violence victimization rates in the country. There can be no doubt that there is a very real problem of non-Indian on Indian domestic violence in Indian Country today. Nonetheless, and regardless of any arguments over the verifiability of statistics in any studies or reports, we should not lose sight of the simple fact that there is no acceptable rate of domestic violence by non-Indian men on Indian women. To argue otherwise is an assault on our national conscience."

-Meteor Blades

• Tribes Contribute More Than $1 Million to Obama: American Indian tribes have generally been quite pleased with how Barack Obama has treated Native matters since arriving in Washington. Consequently, they have collectively contributed more than $1 million to his re-election campaign compared with $264,000 in 2008. They've given Mitt Romney just $3,000. In addition to establishing a Senior Advisor on Native Affairs, pushing to get the Tribal Law and Order Act passed, settling the long-standing Elouise Cobell lawsuit to the tune of $3.4 billion, and settling another $1.1 billion multi-tribal conflict with the federal government over royalties due the tribes, Obama is seen as having achieved a lot for the tribes and, most important, done a lot of listening. He "has done more for Indian country than any president I can remember," said Chief James Allan, chairman of the Coeur d'Alene Tribe in northern Idaho, which donated $35,800 this year to Obama and his joint fundraising committee.

-Meteor Blades

• Important Navajo Taboo, Don't Look at the Sun Today:

![Bahe Whitethorne]()

Painting by Bahe Whitethorne

An annular solar eclipse will be in full view over the Navajo Nation today (Sunday) because it lies directly in the eclipse path. In addition to the common warning not to look directly at the sun's eclipse, Navajos have more rules to follow. Bahe Whitethorne Sr. (Navajo) wrote and illustrated in one of his many children's books called Sunpainters: Eclipse of the Navajo Sun about the taboos to observe while the sun is being eaten.

"The Navajo word for eclipse is 'eating the sun.' In the Navajo tradition it is believed that the 'sun dies' during a solar eclipse and that it is an intimate event between the Earth, Sun and Moon.

"People are told to stay inside and keep still during the dark period. There's no eating, drinking, sleeping, weaving or any other activity. Traditionalists believe that not following this practice could lead to health problems and misfortune to the family."

Once the Na'ach'aabii - the Little People - have repainted the sun and all the colors of the earth, you can resume your activities.

-navajo

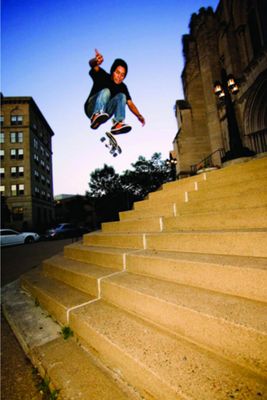

• Tribe Works to Resurrect Game of Cherokee Marbles:

![Two women in Cherokee marbles game]()

Nan Davis and her daughter Andrea Cochran compete in an elimination round of Cherokee Marbles in 2011. (Photo by Will Chavez)

The Cherokee Nation seeks to bring back various cultural traditions of the tribe. Among other things, it's just graduated its first class at an immersion school to teach children their native tongue so they become fluent at a young age. It's also bringing back Cherokee marbles (

di-ga-da-yo-s-di in the Cherokee language), a game that may date to 800 CE or earlier. The traditional stone marbles are much larger than modern marbles, and some carvers have turned them into an art form. But they're expensive and they can crack, so

today's players men and women typically use billiard balls. The playing field is a five-hole course in an L shape covering about 100 feet. It's like croquet (without the mallets) and bocce ball and golf (without the clubs) all rolled into one. The Cherokee Nation holds annual tournaments in September for the Cherokee National Holiday, but more and more people are playing the game casually at family get-togethers.

-Meteor Blades

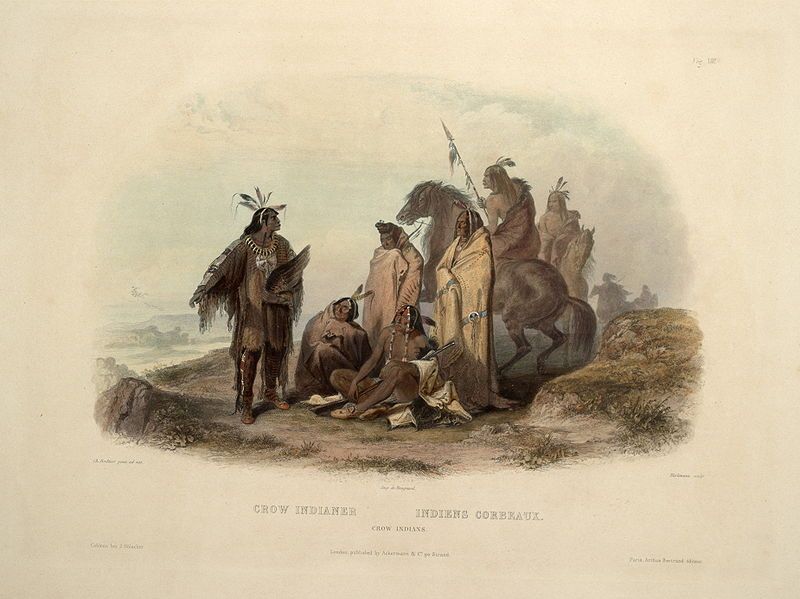

• Indian Students Touch Their Culture in Wyoming Museum: Twice a year, students from the 128-year-old St. Labre Indian School next to the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Ashland, Montana, travel to Cody, Wyoming, to get a first-hand look at Native items housed at the Plains Indian Museum. In addition to their teachers, three Cheyenne elders accompany the students to Cody to pray for them and protect them on their journey. Many of the items the students see and touch have never been on public display. Levi Bixby (Northern Cheyenne) said he recognized the tribal colors on a horse ornament because he had learned beadwork from his grandmother. "I've learned, over the years, the difference between Cheyenne, Crow and Lakota, and I've kinda picked up on other things like Cree; they use flowers, and I do find it interesting, and I do love it because it's part of my heritage." He wants to learn as much as he can about his tribal history and culture, so he can pass along his heritage to his kids and grandkids, "...so we don't fade away."

-Meteor Blades

• Oregon Bans Indian Mascots at Schools:

![Banks High School (Oregon)]()

Banks High School (Oregon) "Brave"

Six years after it adopted a non-binding resolution urging an end to the use of Indian nicknames and mascots at the state's high schools, the Oregon Board of Education voted Thursday to ban their use. The eight schools that still use Indian mascots and names have until 2017 to get rid of them. Seven other schools calling themselves "Warriors" can keep the names but must change mascots and graphics if they depict Indians. Se-ah-dom Edmo (

Shoshone-Bannock/ Nez Perce/ Yakama), vice president of the Oregon Indian Education Association, told the board before the 5-1 vote that the nicknaming practice "is racist. It is harmful. It is shaming. It is dehumanizing." The nicknames and graphics must be removed from uniforms, sports fields, websites, trophy cases and school stationery. Schools that do not comply will face funding reductions. The Philomath School Board

will vote on a resolution Monday objecting to the ban. Its high school mascot is "Warriors" and its middle school uses "Braves," both with depictions of American Indians.

-Meteor Blades

• Ethnic Studies Ban in Arizona Not Keeping Indians Out Native Classes: Arizona's public and charter schools now prohibit ethnic studies. But students in the state can still enroll in classes that include Indian content because both federal and state statutes require it. The state specifically bars classes that are said to promote the overthrow of the U.S. government or create resentment toward a race or class of people, those meant to create ethnic solidarity or designed for specific ethnic groups. Debora Norris (Navajo), director of the Arizona Department of Education's Office of Indian Education, says that since the law passed 17 months ago, she has received calls, letters and e-mails from Indian parents worried about how the it will affect their children. The influx of questions was so great that her office issued a statement pointing out the statute's exemption for Native students as long as the classes are open to all students and do not incite a rebellion against the federal government or hatred toward races or classes. She pointed out that another state law requires school boards to "incorporate instruction on Native American history into appropriate existing curricula." But she concedes that she doesn't know how many schools are in compliance. Of the more than one million students enrolled in Arizona, about 65,000 are Indian, mostly Navajo. About 100 of the 2200 schools in the state are all-Indian.

-Meteor Blades

• School Board Nixes Lakota Honor Song at Graduation:

![Photo of Lakota drum by Ardis McCrae/Native Sun News]()

(Photo by Ardis McCrae/Native Sun News)

The non-Native school board of Chamberlain, S.D., has rejected a request for the honor song to be performed at high school graduation this year on the grounds that it is religious in nature. Chamberlain sits between two "Sioux" reservations, Crow Creek (

Lakota/Dakota) and Lower Brulé (

Kul Wicasa Oyate), separated only by the Missouri River. Total population of the two reservations is about 3500. Jim Cadwell (

Santee Sioux), who grew up at Crow Creek, made the request. He told the weekly Lakota newspaper,

Native Sun News, "There has never been such a ceremony before, and I didn't just ask for the Native kids, I asked the school board to have an honor song for all of the seniors." The rejection based on the song's being religious in nature doesn't wash, Cadwell said, because Chamberlain High School's annual baccalaureate is a pre-graduation religious service. Cadwell decried the "double standard." "I told them they can't have it both ways." Nineteen of the 50 seniors set to graduate this year are Indian, bused in from the two reservations.

-Meteor Blades

• University of Denver Funds Student Powwow to Improve Inclusiveness Image: The University of Denver and Lambda Chi Alpha are making efforts to ameliorate the damage caused by the "Cowboys and Indians"-themed party two Greek houses threw last February. Members of the Native Student Alliance were offended by the party that encouraged participants to wear "Indian" costumes and makeup. The NSA declared this to be yet one more offense to add to DU's lengthy pattern of racial insensitivity toward its American Indian community. As we reported, a pro forma apology was made by Lambda Chi Alpha and Delta Delta Delta to the NSA in March. A hundred NSA and local Indian community members gathered, but only the two Greek house representatives showed up to deliver the apology.

The DU administration recently allocated $6,500 to the NSA for its 2nd annual powwow. It was designated as a DU Presidential Debate signature event under the name New Beginnings Spring Powwow.

The Lambda Chi Alpha hosted an information booth during the powwow to show its support of the NSA as well as the greater American Indian community. Members passed out flyers giving background information and a history of the powwow.

This large donation raised the powwow to competition status, which, it was hoped, would encourage larger turnout and more contestants. Vendors were given free booth space.

-navajo

• American Indian Population Increases: The Census Bureau has estimated there are 6.3 million people designating themselves as American Indian in the United States as of 2011. That's up 2.1 percent from 2010. The problem with the count is that it is self-designation. The total is far more than the number of Americans who are enrolled or otherwise associated with a recognized or unrecognized tribe. The report stated California had the highest number of American Indians with about 1,050,000. Alaska had the highest ratio of Natives, at 19.6 percent. At 93.6 percent, Shannon County, S.D., home to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, had the highest percentage of Indians of any county. And Los Angeles County, larger than Delaware and Rhode Island combined, had the highest number of Indians, with around 231,000.

-Meteor Blades

• 'Twilight' Star Chaske Spencer Pushes American Indian Vote: Spencer (Fort Peck-Lakota/Nez Perce/Cherokee/Creek), known for his work to improve Indian lives, has with Native Vote in a new video. Native Vote is a non-partisan initiative of the National Congress of American Indians.

Video will not embed here.

Visit http://www.youtube.com/embed/w...

-Meteor Blades

• Oglala Sioux Tribe Veterans Cemetery Approved: A $6 million tribal veterans cemetery on the Pine Ridge Reservation will allow Oglalas to hold traditional ceremonies for military veterans beginning in the spring or summer of 2013. The burial grounds will allow for Lakota ceremonial rites that aren't permitted at other veterans cemeteries. Talli Naumann of Native Sun News reports that Lakota traditions such as horseback escorts of the deceased and the ritual of taking food to the interment site to feed the dead will be kept in mind by the architects in their design. In addition, the cemetery will include provisions for burial scaffolds that allow traditional blessings to be offered before interment and a shelter designed as a medicine wheel. In keeping with custom, the cemetery's entrances and all its buildings will be located on the east side.

-Meteor Blades

• Native Language Advocate Dies at 88: Tim Parsons, the first director of Humboldt State University's Community Development Center, which became the Indian Community Development Center at the California university, has died. Over several decades he tirelessly sought to keep American Indian languages alive in the Pacific Northwest. Among other things, Parsons helped develop a phonetic alphabet for the Hupa, Karuk, Tolowa and Yurok languages that had previously been passed down solely through the spoken word. He also developed textbooks and curriculums to facilitate formal teaching of the languages.

-Meteor Blades

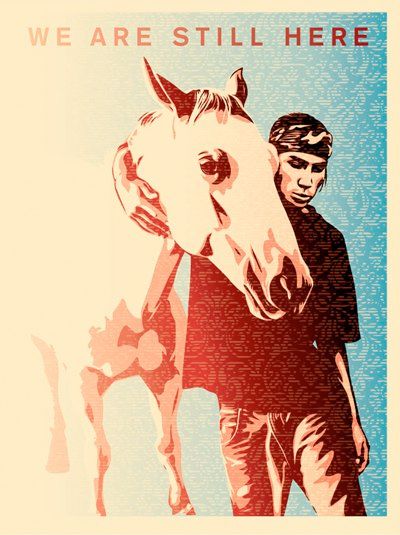

![red_black_rug_design2]()

Indians have often been referred to as the "Vanishing Americans." But we are still here, entangled each in his or her unique way with modern America, blended into the dominant culture or not, full-blood or not, on the reservation or not, and living lives much like the lives of other Americans, but with differences related to our history on this continent, our diverse cultures and religions, and our special legal status. To most other Americans, we are invisible, or only perceived in the most stereotyped fashion.

First Nations News & Views is designed to provide a window into our world, each Sunday reporting on a small number of stories, both the good and the not-so-good, and providing a reminder of where we came from, what we are doing now and what matters to us. We wish to make it clear that neither navajo nor I make any claim whatsoever to speak for anyone other than ourselves, as individuals, not for the Navajo people or the Seminole people, the tribes in which we are enrolled as members, nor, of course, the people of any other tribes.

tags:

Native American Netroots, First Nations News, American Indian, Civil Rights, First Nations, First Nations News & Views, Invisible Indians, Native American, Racism, Indians 101,